Some films are agonizingly frustrating because they have the potential to be not just good, but great and didn't turn out that way. Harry Langdon's "Long Pants" is one such film.

Oh, let's make no mistake, it is a first-rate comedy, but there's so much about it that one has to ask "Why did they (all those involved in the making of the film) do this?"

For one thing, at least one sequence in

the picture could be considered "black comedy," and

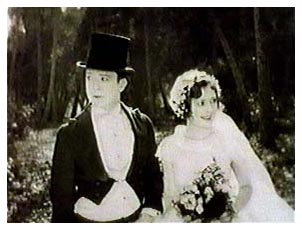

that just isn't suited to Harry Langdon. Priscilla, the adorable

girl next door, is enamored of Harry, and their wedding day has

arrived with all of the friends, family and neighbors filling

the house in the midst of this festive atmosphere. Harry still

hasn't gotten over the kiss from "city siren" Bebe Blair,

and when he sees in the newspaper that she has been sent to jail,

he  vows to go to her side. But this

is his wedding day, and, his father logically asks, "How

are you going to get out of it now? It's too late." This

is where the story begins to unsettle us rather than entertain

us. Harry spies his father's pistol and decides the only way to

get out of the marriage is to kill Priscilla. At this point, we

have to stop and ask ourselves, "Is this a Harry Langdon

comedy?" Besides, whatever happened to the time-honored tradition

of just being a cad and running out while the bride stands waiting

at the alter?

vows to go to her side. But this

is his wedding day, and, his father logically asks, "How

are you going to get out of it now? It's too late." This

is where the story begins to unsettle us rather than entertain

us. Harry spies his father's pistol and decides the only way to

get out of the marriage is to kill Priscilla. At this point, we

have to stop and ask ourselves, "Is this a Harry Langdon

comedy?" Besides, whatever happened to the time-honored tradition

of just being a cad and running out while the bride stands waiting

at the alter?

Once Harry gets Priscilla in the woods for the dastardly deed, there are, admittedly, some funny sequences. Probably the best is a pure slapstick sequence in which Harry's top hat gets pushed down over his eyes and stuck. He gets tangled in barbed wire and finally gets his foot stuck in a bear trap. The trap is connected to a flimsy little tree, and every time Harry jerks the trap with his leg, the tree is pulled over and slaps him in the head. Since Harry still has the hat stuck over his eyes, he can't figure out what's going on.

And there are some more funny "bits" in this sequence, but it's as if we're laughing at them with something in reserve, holding back, so to speak, because here's our lovable little comedian who's unbelievably entertaining the thought of murder and actually acting on it! What makes it all the more disturbing is just how adorable Priscilla is portrayed. He asks her to play hide and seek so he can shoot her when she isn't looking. However, before he can do the deed, she finishes counting, runs up and tags him and scampers away. While she is counting another time, he turns, bends over and "slinks" away for another vantage point to get a good shot at her. What he doesn't realize is that she has turned, bent over and is playfully slinking along behind him.

There are only two ways to go if you want to kill someone off in the movie whether it's comedy or drama. You either solicit the audience's sympathy (and sadness) because the person who died is so likeable, or you solicit the audience's approval/acceptance because the person who dies is so despicable. Neither would work here. Of course, Harry did NOT shoot her, and, being the comedy that it is, we knew from the beginning that wasn't going to happen. But the fact that our hero even entertained such a thought, is disturbing.

In his wonderful book The Silent Clowns (Alfred A. Knopf, 1975), Walter Kerr perceptively points out a misconception that contributed to Langdon falling out of favor with audiences. He said the "ambiguity" of Langdon's character was what made it work. That is, he was a man acting as a child. If he was ever totally a man or totally a child, the character wouldn't work. When Langdon takes Priscilla in the woods to shoot her, this is totally a man, not a man acting as a child. Also, this childlike mentality also allowed him to do things as a man that we forgave, because of his childlike innnocence and inability to understand the seriousness of what was going on. For example, later in the film when he assists Bebe in her robberies, we are led to believe that Harry doesn't really understand what he is helping her do. On that basis, we can accept Harry breaking the law and assisting in the thefts.

In spite of this, there is much of what made Langdon so likeable included in this film. For example, when he puts on his first pair of long pants, he stands in front of the mirror examining himself, primping and happily admiring this new-found symbol of manhood. Then we see him pretend to embrace and kiss a girl. This isn't side-splitting humor, but it's what Langdon did so well the mannerisms, the face, the look.

The sequence where he discovers Bebe in her limousine is classic Langdon, too. He rides his bicycle in front of the limousine, dismounts, and stands there staring at this beautiful, exotic woman. She hasn't even noticed he's there, but he proudly looks down at his long pants, hitches them up, brushes them off, then props one leg up on the bicycle seat in a very GQ kind of pose. When Bebe looks disinterestedly his way, he stands erect and tips his hat. He's so entranced by her, he doesn't notice the bicycle has fallen, and, when he goes to prop his leg up again, the bicycle isn't there, and he falls flat. Also, the man-boy characterization that IS Langdon comes through as he rides his bicycle around and around the limousine performing all sorts of tricks for her. This is when Langdon is both charming and funny.

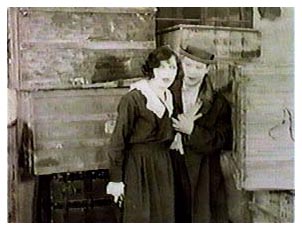

Another sequence has

Harry eluding the police with Bebe in a large crate he is carrying

on his back. He sets it down outside a theatre and walks off for

a minute. While he is gone, a stagehand places a dummy policeman

on the crate and goes back inside. When Harry sees the "policeman,"

he thinks he's real and is afraid to approach the crate. He tries

several tricks to get the "policeman" to leave, but,

obviously, he isn't going anywhere. Finally, he sees the stagehand

come out and remove the dummy. As Harry looks the other way, a

real policeman comes and sits down on the crate. When Harry looks

back up, he thinks the stagehand has put the dummy back. He then

picks up a brick, throws with all his might, and hits the policemen

on the side of the head knocking him to the ground. Obivously,

the obligatory chase ensues. Again, fine comedy and just the kind

of stuff we like to see in a Langdon film.

Another sequence has

Harry eluding the police with Bebe in a large crate he is carrying

on his back. He sets it down outside a theatre and walks off for

a minute. While he is gone, a stagehand places a dummy policeman

on the crate and goes back inside. When Harry sees the "policeman,"

he thinks he's real and is afraid to approach the crate. He tries

several tricks to get the "policeman" to leave, but,

obviously, he isn't going anywhere. Finally, he sees the stagehand

come out and remove the dummy. As Harry looks the other way, a

real policeman comes and sits down on the crate. When Harry looks

back up, he thinks the stagehand has put the dummy back. He then

picks up a brick, throws with all his might, and hits the policemen

on the side of the head knocking him to the ground. Obivously,

the obligatory chase ensues. Again, fine comedy and just the kind

of stuff we like to see in a Langdon film.

However, in spite of all the good bits of business here, we still leave the film dissatisfied and one of the greatest sources of dissatisfaction is the way the whole story comes to an end. After the series of robberies, Bebe, with Harry still dumbly tagging along, goes to the dressing room of the girl who "squealed" on her to the police. Harry sits incredulous as the two women angrily exchange words (no titles are given, as what they say is probably best left to our imagination). Then they fight, which, wisely enough, is not shown. All we see is a fade-out, then Bebe standing over the beaten girl, both of them very disheveled and the room in disarray. Somehow, Harry sat through all of this perfectly motionless. We only see his back as Bebe approaches him, but he shows not the slightest sign of movement. Finally, he gets up, turns and stares at Bebe for what seems to be a very long time. At this point, he tells her he's "surprised" at her, and it's over between them. After such a "heavy" sequence, are we supposed to find this funny?

It was a wise decision not to portray the fight on the screen as that would have made the sequence even more serious, and less amenable to the subsequent "comedy" than it was. However, after Harry says he's leaving, the guy who squealed on Bebe comes in and they have a shootout. Although the fight between the two women was wisely left to our imagination, we are actually shown Bebe and the man falling to the floor after they shoot each other. After the crowd comes into the room, we see a close-up of Harry, cowered on the flooor holding his arm where he was grazed by a bullet, staring in complete bewilderment at the confusion going on about him. Unfortunately, there's nothing funny about any of this. The whole sequence would have been much better served by the old ploy of having the lights go out while we see blasts of gunfire in the darkness . . . or maybe the smoke from the guns obscuring our view so we don't actually see what happens to Bebe or the guy. Also, why was Harry shot in the arm . . . to gain our sympathy? As would be expected, Harry is taken to jail, but the comedy would have been better served if we had seen him flee the melee through a window and run, scared out of his wits, all the way home.

Finally, Harry walks in his front door and

finds his mother, father and Priscilla sitting at the table, heads

bowed, saying grace. He joins them, and, when they look up, they

happily embrace him and welcome him home. This is not exactly

a satisfying end to his adventures, either, because we've lost

some of our sympathy for the character. Did he deserve to return

to such a homecoming? It's hard to put out of our minds that he

once considered killing this lovely girl who so excitedly is welcoming

him home and so faithfully waited for his return. It's also hard

to put out of our minds the hard-boiled experiences he has just

returned from. For  example, we can only

assume Bebe was killed in the gunfire. Is this appropriate for

a comedy? If Langdon was so hung up on pathos, why not a sequence

where Bebe was finally caught again by the police, tells Harry

goodbye and, because of what they went through together, really

started to like him? Then, Harry could be threatened with a long

jail term, but is released, and, so scared by this close brush

with tragedy, he literally runs home very repentent for what he's

done.

example, we can only

assume Bebe was killed in the gunfire. Is this appropriate for

a comedy? If Langdon was so hung up on pathos, why not a sequence

where Bebe was finally caught again by the police, tells Harry

goodbye and, because of what they went through together, really

started to like him? Then, Harry could be threatened with a long

jail term, but is released, and, so scared by this close brush

with tragedy, he literally runs home very repentent for what he's

done.

Kevin Brownlow said in The Parade's Gone By (University of California Press, 1968) that "Long Pants" and "The Strong Man" were Langdon's best features, and that may be true, although "His First Flame" is very enjoyable, too. Brownlow also noted that the relationship between Langdon and director Capra, which had been so successful on these three features, was beginning to deteriorte during the making of "Long Pants." After this picture, Langdon fired Capra. Many claim that this came about because the success of his previous pictures had gone to his head. Whatever the reason, "Long Pants" seemed to have suffered because of this failing relationship. ""Long Pants" . . . inexplicably lost the polished veneer of "The Strong Man,"" Brownlow said. "It remains an important comedy, and often a highly successful one. But the final result indicates that something was wrong somewhere."

Certainly, Langdon deserves to be revered

as one of the best comedians of the silent era, but, for the novice

who is first being introduced to this man, it is best to start

at the beginning of his career with Mack Sennett and see his films

in the order they were made. The development of a first-rate comedian

can be observed, and the two-reelers he made for Sennett are some

of the best comedy to come out of the silent era. After seeing

these, the viewer is better able to appreciate Langdon's style

of humor in a feature format, and can better appreciate "Long

Pants" while knowing he was much better than this movie allowed

him to be.

copyright 2000 by Tim Lussier, all rights reserved